Section 4.5 Projects for Second-Order Differential Equations

Subsection 4.5.1 Project—Tuning a Circuit

https://www.simiode.org/resources/2848.| Spring-Mass Model | RLC Circuit |

| mass m | inductance L |

| damping b | resistance R |

| spring constant k | inverse of capacitance 1/C |

| forcing function f(t) | derivative of induced voltage E′(t) |

Subsubsection Simple RLC Circuit Model, Solution, and Interpretation

We now examine a circuit in which a current is present and does not have a driving E(t), expecting things to dampen out, in this case current to run out. Let us consider an RLC circuit as depicted in Figure 4.1.1 in which we have an initial current, I(0)=3.2 amps with a resistance of R=7 ohms, an inductance of L=1 henry, and a capacitance of C=0.1 farads. Since we have some current in the circuit already I(0)=3.2 at the start we shall not need an inducing E(t), so E(t)=0. Let us see what happens to the current in the circuit by solving the appropriate RLC circuit differential equationActivity 4.5.1.

(a)

Solve the RLC circuit differential equation (4.5.2) for I(t). If you use Sage to solve this equation, remember that I is the reserved symbol for i, the square root of −1.

(b)

Consider the values of R to be 0.007, 0.07, 0.7, 7, 70, and then 700, and solve (4.5.2) in each case, keeping all other values the same. Plot the solutions for the current in the circuit over the time interval [0,25] s with a vertical plot interval [−3,3] in each case. Identify each plot with its associated R value and describe what is happening to the current, I(t), in each corresponding circuit over time, t.

xxxxxxxxxxt =var('t');y = function('y')(t); L = var('L'); assume(L < 0)R = var('R'); assume(R > 5)C = var('C'); assume(C > 5)assume(C*R^2 + 4*R^2 - 4*L - 400 >0) omega = var('omega'); assume(omega > 0)DE = L*diff(y,t,2) + R*diff(y,t) + y/C == omega*cos(omega*t)sol = desolve(DE, y, ivar = t, ics=[0, 0, 0])sol.show()Subsubsection Trigonometry Pause and Phase Angle

The initial value problem

Activity 4.5.2.

(a)

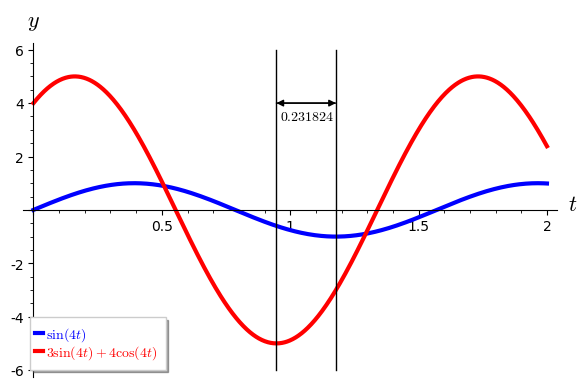

Solve the initial value problem

(b)

Convert the solution to phase angle format and compute the phase angle θ in radians.

(c)

Plot both solutions in Task 4.5.2.a and Task 4.5.2.b on the same axis over the interval [0,2] to confirm your analysis. What should you see?

Subsubsection Back to the Circuit

In our study of phase angle representation in the previous section we saw that the sin(ωt) and cos(ωt) terms of (4.5.4) can be combined into one sine term (albeit with a phase angle) with one amplitude,

Activity 4.5.3.

(a)

Use your understanding of RLC circuits to show for an imposed E(t)=sin(ωt) on the RLC circuit given by

the maximum gain is obtained when ω=1/√LC and thus we could tune our radio by changing the inductance L as well, if that were as convenient as changing the capacitance, which it is not. So let us stick to tuning by changing the capacitance C.

Activity 4.5.4. Tune the Radio.

The Amplitude Modulated (AM) radio carrier frequencies are in the frequency range 535–1605 kHz. One Hz means 1 cycle per second while kHz means 1,000 cycles per second. The unit Hz is called a hertz. Carrier frequencies of 540 to 1600 kHz are assigned at 10 kHz intervals. The (Frequency Modulated (FM) radio band is from 88 to 108 MHz. 25 Recall 1 kHz means 1,000 cycles per second. So 660 kHz is oscillation at the rate of 660,000 cycles per second. We offer up a “radio”,

where E(t)=sin(ωt), and ask you to tune in several stations by changing the capacitance and computing the optimal gain for these stations.

http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/audio/radio.html Accessed 18 September 2016.We will have to tell the circuit what initial current is present; i.e., I(0)=0 usually until we turn the switch on and also we can presume there is no change in the current intially; i.e., I′(t)=0. Let us build this radio with the following values: E(t)=sin(ωt), L=0.033 henrys, R=100 ohms, and C in farads can vary as needed to tune to various input frequencies ω. We note that if we wish to have, say 540 kHz, then ω=540,000⋅2π, and in general to have x kHz we will need ω=x⋅1000⋅2π.

(a)

Solve the differential equation (4.5.10) for the radio circuit.

(b)

Collect the coefficients A and B of the steady state sin(ωt) and cos(ωt) terms, respectively. Show that all other terms will dissipate, i.e. go to zero quickly, leaving only sin(ωt) and cos(ωt) terms.

(c)

Using the information above compute the gain as a function of capacitance C and input voltage frequency ω.

(d)

For a given input voltage frequency ω determine the maximum gain for this circuit.

(e)

For several AM frequencies, say 540 kHz (ω=540000⋅2⋅π), 880 kHz (ω=880000⋅2⋅π), and 1520 kHz (ω=1520000⋅2⋅π), plot gain as a function of the capacitance C to demonstrate that your maximum gain is what your formula in Task 4.5.4.c predicts and that your radio is tuned in.

Subsection 4.5.2 Project—Hanging Mass and Rubberband

Subsubsection The History of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge

On July 1, 1940, the Tacoma Narrows Bridge was completed and opened to traffic (Figure 4.5.6). From the first day of operation, the bridge experienced vertical oscillations of several feet. The bridge received the nickname “Galloping Gertie” for its wild behavior. On the morning of November 7, the bridge began undulating up and down with motions as large as three feet. Later, the bridge began to experience torsional oscillations as large as 23 degrees. The bridge finally came crashing down at 11:10 a.m. For a long time, the collapse of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge was attributed to resonance. However, we shall soon see the the story is more complicated.

Subsubsection The Design of the Narrows Bridge

The Tacoma Narrows bridge is a suspension bridge like the Golden Gate bridge. The road bed of the suspension bridge was hung from vertical cables attached to other cables strung between the two towers. If we think of the cables as long springs, it is tempting to model the oscillations of the road bed with an harmonic oscillator, and one's first guess as to the reason for the collapse of the bridge would be resonance. However, the answer may not be so simple. If the collapse of the bridge was due to resonance, the forcing frequency of a forced harmonic oscillator must be close to its natural frequency, but the wind (the forcing) simply does not behave like this. One explanation might be the fact that cables are not true springs. They act more like rubber bands. Imagine a mass suspended by both a spring and a rubber band. The rubber band acts like a spring when it is stretched, but there is no restoring force if the oscillator is in a compressed position (Figure 4.5.7). 27Subsubsection The Spring-Rubber Band Model

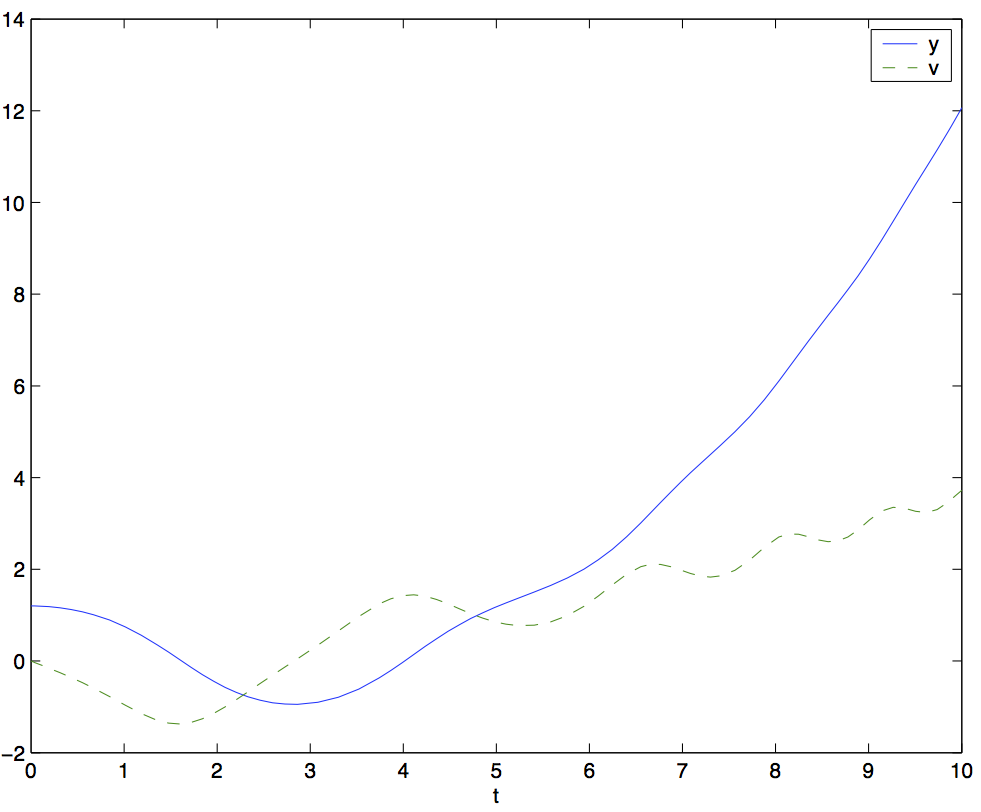

Suppose that y(t) is vertical displacement of the mass the spring-rubber band model (Figure 4.5.7), where the displacement is positive in the downward direction and negative in the upward direction. We will also assume that we have a damped system. If this is the case, we can model the motion of the mass with the differential equation

Subsubsection The Bridge Model

We can now model the bridge by- y is the height of the road bed at the center of the bridge.

- m is the mass of the bridge.

- \alpha y' is the damping term. We assume that \alpha is small since suspension bridges are relatively flexible structures.

- \beta y is the force provided by the material of the bridge pulling the bridge back to y = 0\text{.}

- \gamma y^+ is the force provided by the pull of the cables.

- -gm is the force provided by gravity.

- F(t) is the periodic force provided by the wind. Yes, wind does provide a periodic force. Just think of how a flag flutters in a wind.

Subsubsection The Model for Torsion

We have still not accounted for the large torsional oscillations that occurred on November 7, 1940, the day that the Tacoma Narrows bridge collapsed. If we look down the bridge (Figure 4.5.6), we see the road bed suspended from two cables—one on each side of the road. Thus, we can view a cross-section of the bridge as a rod suspended by cables or springs on each end. The bar is free to move vertically and rotate about its center of mass. If a spring with spring constant k is extended by a distance y\text{,} the potential energy is ky^2/2\text{.} Let \theta be the angle of the rod from the horizontal. If a rod of mass m and length 2l rotates about its center of gravity with angular velocity d\theta/dt\text{,} then its kinetic energy is given by 28